Jack the Ripper Special Branch Index Ledgers

Fri Sep 02, 2011 7:17 am by Admin

Where would a book on Jack the Ripper conspiracies be without mention and an adequate assessment of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch Index Ledgers?

For those who do have a personal interest in these developments on the case, details on their existence and relevance was first published in the foundational reference work on the Whitechapel murders in 2006, Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard …

For those who do have a personal interest in these developments on the case, details on their existence and relevance was first published in the foundational reference work on the Whitechapel murders in 2006, Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard …

Comments: 0

Secret Files on Jack the Ripper?

Wed May 18, 2011 3:36 pm by auspirograph

Breaking News?

Hi all,

Yes, this is a breaking story on Jack the Ripper historical sources but it has been an on-going saga for some time with the UK Information Tribunal. The story is a bit more involved than the press are reporting, or as Trevor Marriott is describing. There are certainly some details of a Victorian Special Branch investigation of Jack the Ripper, however, because suspects …

Hi all,

Yes, this is a breaking story on Jack the Ripper historical sources but it has been an on-going saga for some time with the UK Information Tribunal. The story is a bit more involved than the press are reporting, or as Trevor Marriott is describing. There are certainly some details of a Victorian Special Branch investigation of Jack the Ripper, however, because suspects …

Comments: 5

Ripper Writers RSS Feeds

Wed Aug 25, 2010 4:56 pm by Admin

As a service to members and guests of Jack the Ripper Writers who would like to subscribe to updates and news displayed on this website blog, please go to the menu right and choose your favorite option.

Thanks for your continued interest and support of a site specific for writers, authors and crime historians on Jack the Ripper and the iconic Whitechapel murders.

Admin

Jack the Ripper Writers

Thanks for your continued interest and support of a site specific for writers, authors and crime historians on Jack the Ripper and the iconic Whitechapel murders.

Admin

Jack the Ripper Writers

Comments: 0

THE INDICTMENT

by

Joe Chetcuti

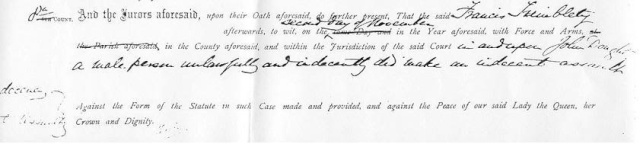

The Public Record Office was located at Chancery Lane in London when Andy Aliffe journeyed there in 1995 and discovered a document dating back to November 1888. The sheet was a handwritten indictment from the Marlborough Street Police Court pertaining to charges brought against the “Jack the Ripper” suspect, Francis Tumblety. The defendant was embroiled in a misdemeanor criminal case that involved four counts of gross indecency, four counts of indecent assault and four alleged victims. According to the court calendar, those offences were committed on four separate dates ranging over a three-month period.

Tumblety was taken into custody for the offences on November 7, 1888. In all likelihood, he was released on bail shortly thereafter. On the following Wednesday, he was issued a ‘committal warrant to trial’ and was jailed. Two sureties bailed him out of his trouble on Friday, November 16th, and it can be reasonably assumed that the indictment paper discovered by Andy Aliffe was authorized on November 19th. (1)

The indictment against Francis Tumblety.

When taking a look at the indictment, our eyes soon settle on the names John Doughty, Arthur Brice, Albert Fisher and James Crowley. Over the years we have grown accustomed to hearing about this quartet. Yet somewhat surprisingly, it has been a difficult task for researchers to obtain personal information on those alleged victims. Chris Scott, however, may have hit upon a lead. He came across a van-boy named Arthur Brice who lived at 11 Hyde Road, Hoxton, in 1896. He once appeared as a witness at the Old Bailey. It can’t be said with any certainty that this Arthur Brice was the same person whom Tumblety supposedly violated on August 31, 1888, but it is a possibility.

Continuing down, we see the names Frank Froest and Walter Dinnie on the charge sheet. Both men advanced splendidly in their law enforcement careers. Froest became the Superintendent of the C.I.D. in 1906, and Dinnie eventually attained the position of “Commissioner of Police” in New Zealand. Even though the court document mistakenly shows Froest to have been a PC in 1888 the man was actually a Detective Sergeant at the time. He gained valuable experience while working under John G. Littlechild, the Special Branch chief whose personal opinion of Tumblety is well-known. If Froest and Dinnie were involved in Tumblety's arrest in November 1888, then it figured that their names would have appeared on the indictment.

There are two other names on the sheet. One was listed at the very top of the indictment, and the other at the bottom. The name on the bottom is different from all the rest because it is a personal signature. For some reason, a man named William Sugg signed and underlined his name on this court paper. All the names above William Sugg appeared to have been written in by some clerk of the court whereas William personally autographed his name to the document while using darker ink. So who was William Sugg? Why did only he sign his name to this document? And what were those two little words he wrote just above his signature?

Naturally, those questions led to further questions. Was Mr. Sugg an attorney who represented one or more of the four supposed victims and pressed charges before the magistrate on their behalf? Was he one of Tumblety's sureties? Or was he employed by the Marlborough Street Police Court in some kind of professional capacity — a senior clerk perhaps?

To help find the answers, a small posse of Ripperologists was gathered: Stewart Evans, Simon Wood, and Chris Scott were notified. In addition, Simon was able to recruit the services of his talented researcher in London, Mrs. Sarah Minney. Before long, helpful emails were being exchanged. Thankfully, Stewart steered us to the correct path right away. He had a hunch that Mr. Sugg was William Thomas Sugg, the Managing Director of William Sugg & Company. It was a highly successful firm best known in 1888 for the manufacturing and installation of gas lamps for the streets of London. Sugg's business was headquartered in Westminster, which was not far from the Marlborough Street Police Court, a court whose jurisdiction included the West End of central London. The geography made sense, so William Thomas Sugg became our target for study.

I was happy to communicate with Chris Sugg. He took an immediate interest in our endeavor. I sent him a copy of the charge sheet in question, and he admitted that he had never seen it before. He then added, “I would say that there is no doubt that the signature on the document is that of William Thomas Sugg, my great grandfather.”

If there is one man who is in the best position today to verify the signature of William Thomas Sugg, it would be Chris Sugg. It was good to hear that Stewart’s hunch had paid off. The signature at the bottom of the indictment did indeed belong to William Thomas Sugg, and this had been confirmed by the best authority on the subject. Chris further explained that back in 1869, his great grandfather used to sign his name William T. Sugg, but by 1888 he no longer included his middle initial in his full signature. But when it was required for him to initial something, he would simply jot the letters WTS.

Chris cleverly noticed that his great grandfather had jotted his initials next to the name of one of the four alleged victims on the indictment. In the margin just to the left of the name Albert Fisher, we can see the initials WTS. Of course, further questions immediately arose. Was Albert Fisher a personal acquaintance of William Sugg? Was he an employee of William Sugg & Co. at the time Tumblety was said to have violated him on July 27, 1888? Was that the reason why Sugg placed his initials next to Fisher's name? Besides all of this, Chris was curious, as were we about the two little words his great grandfather wrote above his signature. Nobody was able to make out those words. For the most part, we were pleased about the progress achieved in our research, but there were still some questions that had gone unanswered.

Fortunately a breakthrough ensued when Simon Wood took a stab at deciphering the two mysterious words. He came up with a good plan. Simon instructed one of his researchers to take a look at other Marlborough Street Police Court indictments for the same November period. The researcher did so and promptly emailed the findings. It turned out that William Sugg had signed his name at the bottom of another charge sheet as well. It pertained to a Marlborough Street Police Court case which had nothing to do with the Tumblety matter. Sugg also had placed his WTS initials next to the names of some of the people listed on the indictment. And sure enough, once again Sugg wrote two little words above his signature on this other charge sheet. But fortunately, this time his two little words were clearly legible.

The words were True bill. It was concluded that the two words above Sugg’s signature on Tumblety’s indictment paper must have been True bill, as well. Simon conceived a wise procedure on how to solve our little problem, and as a result an important court document was discovered.

Things quickly fell into place after the words True bill were deciphered. We all agreed that William Sugg had signed his name at the bottom of Tumblety's indictment because he was the foreman of the Grand Jury. By writing the words True bill above his signature, the case was allowed to proceed to the Old Bailey. Simon looked at the American and English Encyclopedia of Law and found a section which constituted Sugg's actions.

Section 25. Foreman's Duties.

The foreman of the Grand Jury is the presiding officer of that body; he is authorized to swear the witnesses who appear before them, and on the finding of an indictment shall indorse the back of it, "a true bill," and sign his name as foreman … The matter of endorsing the indictment a true bill is indispensable, but it is immaterial on what part of the indictment the foreman's name appears.

(The section continued on and it soon revealed the reason why Sugg placed his initials WTS next to the name Albert Fisher.)

“It is also indispensable that the names of the witnesses upon whose testimony the indictment was found shall be indorsed on the indictment."

Elsewhere in the section the instruction was again emphasized that on the finding of an indictment the foreman shall “note thereon the names of all witnesses upon whose testimony the indictment is found.”

So the reason why William Sugg placed his initials next to Albert Fisher's name was because Fisher gave testimony before the Grand Jury. According to the indictment, Fisher was the only man to have testified. This can be said because Sugg did not place his initials beside the name of anyone else. The fact that the Tumblety matter had been presented before a Grand Jury should not be considered a new discovery on our part. Here is a court document that was displayed years ago on the Internet. It was plainly shown that jurors had been involved in this.

I was pleased to inform Chris Sugg that his great grandfather was the foreman of a Grand Jury that voted to have a Ripper suspect's criminal case sent to the Old Bailey. William Sugg and his fellow jurors performed their civic duty during the height of the Autumn of Terror. Chris found all this to be intriguing, and he proudly inserted a “Jack the Ripper” segment on his web site. The mystery of the signature at the bottom of the indictment had been solved. We were now left with one remaining signature. The one at the very top.

Excellent research by Chris Phillips and Mrs. Sarah Minney has taught us much about Mr. Douglas Norman. His full name was Frederick Douglas Norman, and his solicitor’s firm was usually at 4 New Court, Carey Street, London. I’ve never been too keen about presenting genealogy in my articles, but since Frederick is an essential person in our studies, I should make an exception here.

Frederick was born in December 1856 in Richmond, Yorkshire. He was the son of an upholsterer. He first appeared in the Law List when he was 23 years of age, and his name remained there through 1908. He married a woman from Cheltenham, Elizabeth, who was six years his younger. Frederick and his wife had two offspring, but one died at an early age. The surviving child, Doris Violet Douglas Norman was born in London in 1895.

Frederick’s firm took on different names over the years: Douglas Norman Solicitors, Douglas-Norman & Co., Ross & Douglas Norman. (3) His office was located at a prime location in “New Court, Carey Street” adjacent to Lincoln's Inn Fields. It was less than a mile from the Marlborough Street Police Court. As it was, 1888 was a busy year for Frederick. His name often appeared in The Times when he represented clients in police courts. Roger Palmer informed me “It's worth noting that there is a difference between a solicitor and a barrister. At the Old Bailey, a solicitor is not allowed to actually address the court.”

Stewart agreed and added, “Although a barrister was required at the higher court to prosecute or defend a case, this was not so at the police (or magistrates’) court. Cases were prepared and presented by a solicitor at the magistrates' court. The solicitor then briefed a barrister, hence the term 'brief' and the slang term ‘brief’ to describe a lawyer.”

So if you wanted to see Frederick or any of the solicitors of his firm in action in 1888, a site like the Marlborough Street Police Court would have been the place to go. At the top of Tumblety’s indictment, we see that Mr. Douglas Norman was involved in the matter. But there is a big question. Was Frederick the solicitor whom Tumblety hired for his defense? Or did he prosecute the case before the magistrate? A look at The Times in 1888 reveals he was a solicitor who could do both jobs. He handled a wide variety of criminal cases. (4)

* March 14th: Frederick defended a suspected jewel thief. The Treasury pressed charges.

* April 13th: Frederick prosecuted a case on behalf of the Central Vigilance Committee. Two women, who were associated with a brothel, were accused of procuring an under-aged girl.

* May 16th: He defended a woman who was charged with the willful murder of her illegitimate child.

* June 25th: He prosecuted “Prince De Chandernagore” on behalf of the National Vigilance Association. The Prince was charged with unlawfully abducting an unmarried woman, under the age of 18, against the will of the mother.

* August 11th: At Westminister, a Polish Jew was "charged with selling photographs of an improper character in the Brompton road. Mr. F. Douglas Norman prosecuted for the National Vigilance Association.”

* February 15th (1889): He defended a man who assaulted a Police Constable.

So as we can see, Frederick both prosecuted and defended people. But if the case involved sexual immorality, he was most often found representing a vigilance society and pressing charges before a magistrate. Did Frederick represent a vigilance society in the Tumblety case? Did he appear on behalf of Albert Fisher and the other three who were alleged victims of Tumblety’s indecent assault?

It gets interesting when we turn to page 100 of Tumblety's 1893 autobiography. On the page, Tumblety proudly displayed a letter he received from a “distinguished English solicitor” hailing from Lincoln’s Inn Fields (Frederick’s home base). One would think this solicitor would have been Frederick Douglas Norman if Frederick truly was hired for the purpose of Tumblety’s defense. But no. Tumblety displayed a letter which supposedly came from a rival solicitor. The firm was Hutchinson & Sons and not Douglas Norman Solicitors. The solicitor was one of the sons, Elliot Hutchinson, a man who had spent much time in America.

Extract from a letter of a distinguished English solicitor.

59 LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS,

LONDON, August 6, 1891.

MY DEAR SIR - In perusing a London daily paper I noted your generosity to the poor, and of which I am not the least surprised, as it is only one of many generous acts on your part. Believe me yours sincerely,

ELLIOT HUTCHINSON

It makes one wonder if the showcasing of this letter was Tumblety’s way of jabbing at the Douglas Norman firm of solicitors. Did this letter appear in the autobiography because Frederick was a Lincoln's Inn Fields solicitor who pressed charges against Tumblety? Was that the reason why this vindictive Ripper suspect complimented a rival solicitor who hailed from the same London area?

It was decided that an effort should be made to find the November 1888 paperwork of the Douglas Norman Solicitors firm in the hope that some material from the Tumblety case had been preserved. Since Frederick represented two known vigilance societies in 1888 (the National Vigilance Association and the Central Vigilance Committee), an endeavor was undertaken to find their records. The Central Vigilance Committee was the older one, having been founded in 1883 by the Reverend Hanmer William Webb-Peploe. No surviving paperwork has been found that pertains to this committee. We had no luck finding anything at Kew, the LMA, the City of Westminster Archives, or the Lambeth Palace Archives. I contacted the Webb-Peploe family, but that was to no avail as well.

So we had to turn our attention to the National Vigilance Association. Fortunately, I was able to locate some of the 1888-89 NVA records at an East End venue called The Women’s Library. Last April, Sarah Minney arrived there with her digital camera. The friendly staff handed her a stack of paperwork which contained the “minutes” of NVA meetings held during the autumn of 1888 and early 1889. Sarah took many photos and emailed them to us. The minutes of these meetings contained candid discussions on numerous criminal cases which the NVA prosecuted. These discussions were always categorized under the heading "Legal". Frederick's name was mentioned at times. One of the meetings was held on Tuesday night November 20, 1888 at 267 Strand. Although the time period was perfect, the minutes of this meeting did not include any talk on the Tumblety case. This held true for the minutes of every NVA meeting that had been preserved by The Women's Library. A revealing item concerning Frederick appeared in the minutes of a NVA meeting held on January 15, 1889. It was written:

In the case of Bedwell V. Shew, offence on a girl under 16, it appeared that Mr. Norman had not been present during the hearing of the case; his absence was to be enquired into.

The story continued at a NVA meeting held on February 5, 1889: ". . . it had been for some time found that our solicitor was too busy to attend to our work and it was now proposed to employ a solicitor in the Office who would devote the whole of his time to our work…The carrying out of this arrangement was left to the Legal Committee.”

It certainly looked as if Frederick's days with the NVA were numbered, and this was due to his own neglect of the cases brought to him by the NVA. Our findings at The Women’s Library pointed toward a lack of involvement by the NVA in the Tumblety matter. And by the end of 1888, it sounded like Frederick had no longer given the NVA nor its cause much priority.

This is a good time to take a step back and try to sort out what we have here. I’d definitely say that Frederick did not press charges against Tumblety on behalf of the NVA. We found no documents pertaining to the Central Vigilance Committee, so there is no way to confirm or deny that he represented this group in the indictment. Frederick may have pressed charges on behalf of the police, thus excluding the involvement of any vigilance committee.

But it also seemed possible that we were off-base with the perception that Frederick was the prosecuting solicitor in the case. Maybe the name Mr. Douglas Norman appeared at the top of the indictment because Tumblety hired him. It would not have been unprecedented for Frederick to accept a case like this. A small news bite in The Times on July 18, 1888 had him defending a chemist before a magistrate. The chemist was charged with indecent assault upon a 13-year-old. So Frederick was experienced in defending a client against this charge, and of course Tumblety faced four counts of indecent assault.

After reviewing all the material, we still remained uncertain about Frederick’s role in this. Sadly, we began to run out of ideas on where to search for any surviving documentation that the Douglas Norman Solicitors firm may have kept on the Tumblety case. One idea that came to mind was to check with the Solicitors Regulation Authority. Solicitors have been known to hand over their paperwork to the SRA for over a hundred years. It sounded like a decent plan at first, but Sarah Minney was quick to point out, “Solicitor firms are private, and there is no requirement for them to deposit their records.”

Later, the Contact Centre Administrator at the SRA explained to me that their records office “was not established until 1907. So information about individual solicitors and firms prior to that date can be limited.”

The SRA charges £100 per hour for historical research into its own records, which adds up to 120 quid per hour after the VAT is factored in. Since Frederick was not required to turn over his firm's records to the SRA, and knowing that the material stored by the SRA prior to 1907 is limited, it was decided that a very expensive gamble such as this would probably fail. So we didn’t go through with it. The only alternative route we could think of now was to see if Frederick left any 1888 records with a descendant. To help with this segment of the research, Chris Phillips was called upon.

Useful census information was provided by Chris Phillips. The 1911 census listed Frederick as a 54-year-old solicitor living with his 48-year-old wife. They had been married for 24 years at this point. Their home was in Maidenhead, Berkshire. Their teenage daughter was living with them, along with some servants, so they probably were financially comfortable.

Frederick’s wife died in July 1930 in Cardiff. The following month, a probate ruling awarded £350 to her only surviving offspring, Doris Violet Douglas Norman, age 35. Doris was referred to as a spinster.

Chris Phillips also has found a possible death-date for Frederick in March 1931 in Leeds at the age of 74. Frederick did some traveling in his time. He boarded the ship Cedric in September 1904 for a voyage from New York back to Liverpool. Then in 1923 he was a passenger on a ship that sailed from England to Singapore. And finally, only three weeks before his wife died, Frederick was on a ship heading from Australia to England.

After looking at the data Chris Phillips provided, we are left with an empty feeling because there may not be any direct descendants to contact. Frederick was survived by just one offspring who was an unmarried 35 year old woman in 1930. He seemed to have a fine 43-year marriage, and he saw much of the world. So far there are no indications that he continued to practice law beyond 1911.

I was prepared to end this article with that last paragraph above. I would have added a sincere thank you to the folks who helped me out with the research, and I would have simply sent the text to the New Independent Review for publishing. It would have been sent with a lousy feeling of disappointment because I wasn’t able to conclude whether Frederick had been Tumblety’s prosecutor or defense solicitor at the Marlborough Street Police Court. But fortunately, Chris Phillips wasn't ready to give up. He contacted me and spoke of how it might be possible to identify Frederick's role by comparing Tumblety's indictment with another indictment from the same period. The logic being that we'd search for a highly publicized court case that was sent to the Old Bailey from a police court in London, and then we’d review the indictment sheet for that particular case. On the page where the Grand Jury foreman wrote “True Bill” we'd check the top line to view the solicitor's name. Since it would have been a well-publicized case, we’d then be able to find out what role that listed solicitor played in the matter. The key to all of this was to find a high profile case in London during the late 1880s and track down the indictment paper.

In late May, Chris Phillips emailed me back with a winning idea. He properly figured, “The Lipski case in 1887 should be a suitable one. There was quite a lot about his solicitor, John Hayward, in Martin Friedland’s 1984 book on the case. Lipski was committed for trial at a different magistrates’ court, but I’d hope there would have been a common form for drawing up the indictment. So when I’m at Kew next, I will try to find and photograph Lipski’s indictment.”

That was precisely what Chris did. Within a week I was looking at Lipski’s indictment document on my computer. Lipski’s case was allowed to proceed to the Old Bailey from the Thames Police Court. Here are two photo images which were taken by Chris. The first image is the front of Lipski’s indictment document. The second image is the back of that same indictment document.

As expected, at the bottom of the back page the words True Bill were written by the Grand Jury foreman. And right below those words, we see the foreman's signature. This 1887 court document correlated extremely well with Tumblety’s indictment paper. At the very top of the page the words Solicitor Treasury were clearly shown. Chris explained how this related to the prosecution, and not the defense. On page 23 of Martin Friedland’s book The Trials of Israel Lipski, the author wrote, "A treasury solicitor appeared as the prosecutor when the hearing resumed the following week.”

Lipski’s indictment document from the Thames Police Court and Tumblety’s indictment document from the Marlborough Street Police Court were very similar. Both had the “True Bill” designation above the foreman’s signature. And at the very top of that page, a solicitor was listed. As for the question of whether this was a solicitor for the prosecution or the defense, the Lipski case taught us that it is a prosecuting solicitor who gets featured in that spot on the indictment. I have to conclude that Tumblety’s indictment wouldn't have been any different in this respect. I will say that Frederick Douglas Norman was the prosecuting solicitor in the Tumblety case at the Marlborough Street Police Court.

Chris further pointed out, “It does make more sense for the indictment to specify who was responsible for the prosecution, not who was responsible for the defense. I think this does solve the puzzle of what Frederick Douglas Norman’s role was — though not the puzzle of why he assumed the role.”

Frederick was a Lincoln’s Inn Fields solicitor who had a history of prosecuting these types of sexual immorality cases. At the present time it is unknown if the police, or maybe even the Central Vigilance Committee, hired him. As for Elliot Hutchinson, the Lincoln’s Inn Fields solicitor whom Tumblety featured in his 1893 autobiography, one has to wonder if he was Tumblety’s defense solicitor. £120 per hour isn’t an alluring sum, but that is the price to pay to have the Solicitors Regulation Authority check for any surviving 1888 records for the firms Douglas Norman Solicitors and Hutchinson & Sons.

We have taken a good look at the indictment discovered by Andy Aliffe many years ago. It has been a memorable experience. I personally found it enjoyable to work with an excellent group of colleagues who were very generous with their time.

FOOTNOTES

1. Trevor Marriott’s Doctor at Sea article showed why the indictment would have been authorized on November 19, 1888.

2. http://www.williamsugghistory.co.uk

3. Roger Palmer explained that Frederick’s law partner was Henry J. G. Ross. Their partnership dissolved on December 20, 1890 by mutual consent.

4. Chris Phillips and Chris Scott were instrumental in locating these examples from The Times.

PHOTOGRAPH SOURCES

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3d7/1/1 www.casebook.org

www.williamsugghistory.co.uk/history.htm

http://www.pleasantplaces.biz/authors/webbpeploe_hw.php

http://archidose.org/wp/2003/02/10/women's- library

http://www.opensquares.org/images/lincoln.jpg

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciation goes out to Chris Sugg, Stewart Evans, Roger Palmer, Simon Wood, Chris Scott, Sarah Minney, Robert Linford, and The Women's Library in London. A special thanks goes out to Chris Phillips. And of course, a big round of applause goes to Don Souden for preparing the article for publication in the New Independent Review and Spiro Dimolianis for preparing the article on the Jack the Ripper Writers web site.

(c) Joe Chetcuti 2012

Continuing down, we see the names Frank Froest and Walter Dinnie on the charge sheet. Both men advanced splendidly in their law enforcement careers. Froest became the Superintendent of the C.I.D. in 1906, and Dinnie eventually attained the position of “Commissioner of Police” in New Zealand. Even though the court document mistakenly shows Froest to have been a PC in 1888 the man was actually a Detective Sergeant at the time. He gained valuable experience while working under John G. Littlechild, the Special Branch chief whose personal opinion of Tumblety is well-known. If Froest and Dinnie were involved in Tumblety's arrest in November 1888, then it figured that their names would have appeared on the indictment.

Walter Dinnie (seated at the far left) and his family.

There are two other names on the sheet. One was listed at the very top of the indictment, and the other at the bottom. The name on the bottom is different from all the rest because it is a personal signature. For some reason, a man named William Sugg signed and underlined his name on this court paper. All the names above William Sugg appeared to have been written in by some clerk of the court whereas William personally autographed his name to the document while using darker ink. So who was William Sugg? Why did only he sign his name to this document? And what were those two little words he wrote just above his signature?

Naturally, those questions led to further questions. Was Mr. Sugg an attorney who represented one or more of the four supposed victims and pressed charges before the magistrate on their behalf? Was he one of Tumblety's sureties? Or was he employed by the Marlborough Street Police Court in some kind of professional capacity — a senior clerk perhaps?

To help find the answers, a small posse of Ripperologists was gathered: Stewart Evans, Simon Wood, and Chris Scott were notified. In addition, Simon was able to recruit the services of his talented researcher in London, Mrs. Sarah Minney. Before long, helpful emails were being exchanged. Thankfully, Stewart steered us to the correct path right away. He had a hunch that Mr. Sugg was William Thomas Sugg, the Managing Director of William Sugg & Company. It was a highly successful firm best known in 1888 for the manufacturing and installation of gas lamps for the streets of London. Sugg's business was headquartered in Westminster, which was not far from the Marlborough Street Police Court, a court whose jurisdiction included the West End of central London. The geography made sense, so William Thomas Sugg became our target for study.

William Thomas Sugg.

Fortunately for us, the great grandson of William Thomas Sugg has set up a marvelous web site in honor of William Sugg & Company. His name is Chris Sugg, and I found him to be a very helpful and courteous gentleman. Chris has preserved a huge amount of material regarding the history of his family’s firm. Paperwork, photographs, licenses, etc., Chris has it all. He also knows plenty of personal information regarding the famous men and women in his lineage. He kindly shares much of this information on his web site. (2) This was not the first time Chris has dealt with a Ripper journal. He spoke of having worked in cooperation with Ripperologist several years ago on a report concerning London gas lamps of the 1880s.

I was happy to communicate with Chris Sugg. He took an immediate interest in our endeavor. I sent him a copy of the charge sheet in question, and he admitted that he had never seen it before. He then added, “I would say that there is no doubt that the signature on the document is that of William Thomas Sugg, my great grandfather.”

If there is one man who is in the best position today to verify the signature of William Thomas Sugg, it would be Chris Sugg. It was good to hear that Stewart’s hunch had paid off. The signature at the bottom of the indictment did indeed belong to William Thomas Sugg, and this had been confirmed by the best authority on the subject. Chris further explained that back in 1869, his great grandfather used to sign his name William T. Sugg, but by 1888 he no longer included his middle initial in his full signature. But when it was required for him to initial something, he would simply jot the letters WTS.

Chris cleverly noticed that his great grandfather had jotted his initials next to the name of one of the four alleged victims on the indictment. In the margin just to the left of the name Albert Fisher, we can see the initials WTS. Of course, further questions immediately arose. Was Albert Fisher a personal acquaintance of William Sugg? Was he an employee of William Sugg & Co. at the time Tumblety was said to have violated him on July 27, 1888? Was that the reason why Sugg placed his initials next to Fisher's name? Besides all of this, Chris was curious, as were we about the two little words his great grandfather wrote above his signature. Nobody was able to make out those words. For the most part, we were pleased about the progress achieved in our research, but there were still some questions that had gone unanswered.

Fortunately a breakthrough ensued when Simon Wood took a stab at deciphering the two mysterious words. He came up with a good plan. Simon instructed one of his researchers to take a look at other Marlborough Street Police Court indictments for the same November period. The researcher did so and promptly emailed the findings. It turned out that William Sugg had signed his name at the bottom of another charge sheet as well. It pertained to a Marlborough Street Police Court case which had nothing to do with the Tumblety matter. Sugg also had placed his WTS initials next to the names of some of the people listed on the indictment. And sure enough, once again Sugg wrote two little words above his signature on this other charge sheet. But fortunately, this time his two little words were clearly legible.

The words were True bill. It was concluded that the two words above Sugg’s signature on Tumblety’s indictment paper must have been True bill, as well. Simon conceived a wise procedure on how to solve our little problem, and as a result an important court document was discovered.

William Sugg’s signature at the bottom of an indictment,

November 1888. The words “True bill” can be seen above Sugg’s

signature.

Things quickly fell into place after the words True bill were deciphered. We all agreed that William Sugg had signed his name at the bottom of Tumblety's indictment because he was the foreman of the Grand Jury. By writing the words True bill above his signature, the case was allowed to proceed to the Old Bailey. Simon looked at the American and English Encyclopedia of Law and found a section which constituted Sugg's actions.

Section 25. Foreman's Duties.

The foreman of the Grand Jury is the presiding officer of that body; he is authorized to swear the witnesses who appear before them, and on the finding of an indictment shall indorse the back of it, "a true bill," and sign his name as foreman … The matter of endorsing the indictment a true bill is indispensable, but it is immaterial on what part of the indictment the foreman's name appears.

(The section continued on and it soon revealed the reason why Sugg placed his initials WTS next to the name Albert Fisher.)

“It is also indispensable that the names of the witnesses upon whose testimony the indictment was found shall be indorsed on the indictment."

Elsewhere in the section the instruction was again emphasized that on the finding of an indictment the foreman shall “note thereon the names of all witnesses upon whose testimony the indictment is found.”

So the reason why William Sugg placed his initials next to Albert Fisher's name was because Fisher gave testimony before the Grand Jury. According to the indictment, Fisher was the only man to have testified. This can be said because Sugg did not place his initials beside the name of anyone else. The fact that the Tumblety matter had been presented before a Grand Jury should not be considered a new discovery on our part. Here is a court document that was displayed years ago on the Internet. It was plainly shown that jurors had been involved in this.

The indictment against Francis Tumblety.

I was pleased to inform Chris Sugg that his great grandfather was the foreman of a Grand Jury that voted to have a Ripper suspect's criminal case sent to the Old Bailey. William Sugg and his fellow jurors performed their civic duty during the height of the Autumn of Terror. Chris found all this to be intriguing, and he proudly inserted a “Jack the Ripper” segment on his web site. The mystery of the signature at the bottom of the indictment had been solved. We were now left with one remaining signature. The one at the very top.

Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Excellent research by Chris Phillips and Mrs. Sarah Minney has taught us much about Mr. Douglas Norman. His full name was Frederick Douglas Norman, and his solicitor’s firm was usually at 4 New Court, Carey Street, London. I’ve never been too keen about presenting genealogy in my articles, but since Frederick is an essential person in our studies, I should make an exception here.

Frederick was born in December 1856 in Richmond, Yorkshire. He was the son of an upholsterer. He first appeared in the Law List when he was 23 years of age, and his name remained there through 1908. He married a woman from Cheltenham, Elizabeth, who was six years his younger. Frederick and his wife had two offspring, but one died at an early age. The surviving child, Doris Violet Douglas Norman was born in London in 1895.

Frederick’s firm took on different names over the years: Douglas Norman Solicitors, Douglas-Norman & Co., Ross & Douglas Norman. (3) His office was located at a prime location in “New Court, Carey Street” adjacent to Lincoln's Inn Fields. It was less than a mile from the Marlborough Street Police Court. As it was, 1888 was a busy year for Frederick. His name often appeared in The Times when he represented clients in police courts. Roger Palmer informed me “It's worth noting that there is a difference between a solicitor and a barrister. At the Old Bailey, a solicitor is not allowed to actually address the court.”

Stewart agreed and added, “Although a barrister was required at the higher court to prosecute or defend a case, this was not so at the police (or magistrates’) court. Cases were prepared and presented by a solicitor at the magistrates' court. The solicitor then briefed a barrister, hence the term 'brief' and the slang term ‘brief’ to describe a lawyer.”

So if you wanted to see Frederick or any of the solicitors of his firm in action in 1888, a site like the Marlborough Street Police Court would have been the place to go. At the top of Tumblety’s indictment, we see that Mr. Douglas Norman was involved in the matter. But there is a big question. Was Frederick the solicitor whom Tumblety hired for his defense? Or did he prosecute the case before the magistrate? A look at The Times in 1888 reveals he was a solicitor who could do both jobs. He handled a wide variety of criminal cases. (4)

* March 14th: Frederick defended a suspected jewel thief. The Treasury pressed charges.

* April 13th: Frederick prosecuted a case on behalf of the Central Vigilance Committee. Two women, who were associated with a brothel, were accused of procuring an under-aged girl.

* May 16th: He defended a woman who was charged with the willful murder of her illegitimate child.

* June 25th: He prosecuted “Prince De Chandernagore” on behalf of the National Vigilance Association. The Prince was charged with unlawfully abducting an unmarried woman, under the age of 18, against the will of the mother.

* August 11th: At Westminister, a Polish Jew was "charged with selling photographs of an improper character in the Brompton road. Mr. F. Douglas Norman prosecuted for the National Vigilance Association.”

* February 15th (1889): He defended a man who assaulted a Police Constable.

So as we can see, Frederick both prosecuted and defended people. But if the case involved sexual immorality, he was most often found representing a vigilance society and pressing charges before a magistrate. Did Frederick represent a vigilance society in the Tumblety case? Did he appear on behalf of Albert Fisher and the other three who were alleged victims of Tumblety’s indecent assault?

It gets interesting when we turn to page 100 of Tumblety's 1893 autobiography. On the page, Tumblety proudly displayed a letter he received from a “distinguished English solicitor” hailing from Lincoln’s Inn Fields (Frederick’s home base). One would think this solicitor would have been Frederick Douglas Norman if Frederick truly was hired for the purpose of Tumblety’s defense. But no. Tumblety displayed a letter which supposedly came from a rival solicitor. The firm was Hutchinson & Sons and not Douglas Norman Solicitors. The solicitor was one of the sons, Elliot Hutchinson, a man who had spent much time in America.

Extract from a letter of a distinguished English solicitor.

59 LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS,

LONDON, August 6, 1891.

MY DEAR SIR - In perusing a London daily paper I noted your generosity to the poor, and of which I am not the least surprised, as it is only one of many generous acts on your part. Believe me yours sincerely,

ELLIOT HUTCHINSON

It makes one wonder if the showcasing of this letter was Tumblety’s way of jabbing at the Douglas Norman firm of solicitors. Did this letter appear in the autobiography because Frederick was a Lincoln's Inn Fields solicitor who pressed charges against Tumblety? Was that the reason why this vindictive Ripper suspect complimented a rival solicitor who hailed from the same London area?

It was decided that an effort should be made to find the November 1888 paperwork of the Douglas Norman Solicitors firm in the hope that some material from the Tumblety case had been preserved. Since Frederick represented two known vigilance societies in 1888 (the National Vigilance Association and the Central Vigilance Committee), an endeavor was undertaken to find their records. The Central Vigilance Committee was the older one, having been founded in 1883 by the Reverend Hanmer William Webb-Peploe. No surviving paperwork has been found that pertains to this committee. We had no luck finding anything at Kew, the LMA, the City of Westminster Archives, or the Lambeth Palace Archives. I contacted the Webb-Peploe family, but that was to no avail as well.

The Rev. H. Webb-Peploe, founder of the Central Vigilance Committee.

So we had to turn our attention to the National Vigilance Association. Fortunately, I was able to locate some of the 1888-89 NVA records at an East End venue called The Women’s Library. Last April, Sarah Minney arrived there with her digital camera. The friendly staff handed her a stack of paperwork which contained the “minutes” of NVA meetings held during the autumn of 1888 and early 1889. Sarah took many photos and emailed them to us. The minutes of these meetings contained candid discussions on numerous criminal cases which the NVA prosecuted. These discussions were always categorized under the heading "Legal". Frederick's name was mentioned at times. One of the meetings was held on Tuesday night November 20, 1888 at 267 Strand. Although the time period was perfect, the minutes of this meeting did not include any talk on the Tumblety case. This held true for the minutes of every NVA meeting that had been preserved by The Women's Library. A revealing item concerning Frederick appeared in the minutes of a NVA meeting held on January 15, 1889. It was written:

In the case of Bedwell V. Shew, offence on a girl under 16, it appeared that Mr. Norman had not been present during the hearing of the case; his absence was to be enquired into.

The story continued at a NVA meeting held on February 5, 1889: ". . . it had been for some time found that our solicitor was too busy to attend to our work and it was now proposed to employ a solicitor in the Office who would devote the whole of his time to our work…The carrying out of this arrangement was left to the Legal Committee.”

It certainly looked as if Frederick's days with the NVA were numbered, and this was due to his own neglect of the cases brought to him by the NVA. Our findings at The Women’s Library pointed toward a lack of involvement by the NVA in the Tumblety matter. And by the end of 1888, it sounded like Frederick had no longer given the NVA nor its cause much priority.

The Women’s Library in London.

This is a good time to take a step back and try to sort out what we have here. I’d definitely say that Frederick did not press charges against Tumblety on behalf of the NVA. We found no documents pertaining to the Central Vigilance Committee, so there is no way to confirm or deny that he represented this group in the indictment. Frederick may have pressed charges on behalf of the police, thus excluding the involvement of any vigilance committee.

But it also seemed possible that we were off-base with the perception that Frederick was the prosecuting solicitor in the case. Maybe the name Mr. Douglas Norman appeared at the top of the indictment because Tumblety hired him. It would not have been unprecedented for Frederick to accept a case like this. A small news bite in The Times on July 18, 1888 had him defending a chemist before a magistrate. The chemist was charged with indecent assault upon a 13-year-old. So Frederick was experienced in defending a client against this charge, and of course Tumblety faced four counts of indecent assault.

After reviewing all the material, we still remained uncertain about Frederick’s role in this. Sadly, we began to run out of ideas on where to search for any surviving documentation that the Douglas Norman Solicitors firm may have kept on the Tumblety case. One idea that came to mind was to check with the Solicitors Regulation Authority. Solicitors have been known to hand over their paperwork to the SRA for over a hundred years. It sounded like a decent plan at first, but Sarah Minney was quick to point out, “Solicitor firms are private, and there is no requirement for them to deposit their records.”

Later, the Contact Centre Administrator at the SRA explained to me that their records office “was not established until 1907. So information about individual solicitors and firms prior to that date can be limited.”

The SRA charges £100 per hour for historical research into its own records, which adds up to 120 quid per hour after the VAT is factored in. Since Frederick was not required to turn over his firm's records to the SRA, and knowing that the material stored by the SRA prior to 1907 is limited, it was decided that a very expensive gamble such as this would probably fail. So we didn’t go through with it. The only alternative route we could think of now was to see if Frederick left any 1888 records with a descendant. To help with this segment of the research, Chris Phillips was called upon.

Useful census information was provided by Chris Phillips. The 1911 census listed Frederick as a 54-year-old solicitor living with his 48-year-old wife. They had been married for 24 years at this point. Their home was in Maidenhead, Berkshire. Their teenage daughter was living with them, along with some servants, so they probably were financially comfortable.

Frederick’s wife died in July 1930 in Cardiff. The following month, a probate ruling awarded £350 to her only surviving offspring, Doris Violet Douglas Norman, age 35. Doris was referred to as a spinster.

Chris Phillips also has found a possible death-date for Frederick in March 1931 in Leeds at the age of 74. Frederick did some traveling in his time. He boarded the ship Cedric in September 1904 for a voyage from New York back to Liverpool. Then in 1923 he was a passenger on a ship that sailed from England to Singapore. And finally, only three weeks before his wife died, Frederick was on a ship heading from Australia to England.

After looking at the data Chris Phillips provided, we are left with an empty feeling because there may not be any direct descendants to contact. Frederick was survived by just one offspring who was an unmarried 35 year old woman in 1930. He seemed to have a fine 43-year marriage, and he saw much of the world. So far there are no indications that he continued to practice law beyond 1911.

I was prepared to end this article with that last paragraph above. I would have added a sincere thank you to the folks who helped me out with the research, and I would have simply sent the text to the New Independent Review for publishing. It would have been sent with a lousy feeling of disappointment because I wasn’t able to conclude whether Frederick had been Tumblety’s prosecutor or defense solicitor at the Marlborough Street Police Court. But fortunately, Chris Phillips wasn't ready to give up. He contacted me and spoke of how it might be possible to identify Frederick's role by comparing Tumblety's indictment with another indictment from the same period. The logic being that we'd search for a highly publicized court case that was sent to the Old Bailey from a police court in London, and then we’d review the indictment sheet for that particular case. On the page where the Grand Jury foreman wrote “True Bill” we'd check the top line to view the solicitor's name. Since it would have been a well-publicized case, we’d then be able to find out what role that listed solicitor played in the matter. The key to all of this was to find a high profile case in London during the late 1880s and track down the indictment paper.

In late May, Chris Phillips emailed me back with a winning idea. He properly figured, “The Lipski case in 1887 should be a suitable one. There was quite a lot about his solicitor, John Hayward, in Martin Friedland’s 1984 book on the case. Lipski was committed for trial at a different magistrates’ court, but I’d hope there would have been a common form for drawing up the indictment. So when I’m at Kew next, I will try to find and photograph Lipski’s indictment.”

That was precisely what Chris did. Within a week I was looking at Lipski’s indictment document on my computer. Lipski’s case was allowed to proceed to the Old Bailey from the Thames Police Court. Here are two photo images which were taken by Chris. The first image is the front of Lipski’s indictment document. The second image is the back of that same indictment document.

The indictment against Israel Lipski.

The back of Lipski’s indictment.

As expected, at the bottom of the back page the words True Bill were written by the Grand Jury foreman. And right below those words, we see the foreman's signature. This 1887 court document correlated extremely well with Tumblety’s indictment paper. At the very top of the page the words Solicitor Treasury were clearly shown. Chris explained how this related to the prosecution, and not the defense. On page 23 of Martin Friedland’s book The Trials of Israel Lipski, the author wrote, "A treasury solicitor appeared as the prosecutor when the hearing resumed the following week.”

Lipski’s indictment document from the Thames Police Court and Tumblety’s indictment document from the Marlborough Street Police Court were very similar. Both had the “True Bill” designation above the foreman’s signature. And at the very top of that page, a solicitor was listed. As for the question of whether this was a solicitor for the prosecution or the defense, the Lipski case taught us that it is a prosecuting solicitor who gets featured in that spot on the indictment. I have to conclude that Tumblety’s indictment wouldn't have been any different in this respect. I will say that Frederick Douglas Norman was the prosecuting solicitor in the Tumblety case at the Marlborough Street Police Court.

Chris further pointed out, “It does make more sense for the indictment to specify who was responsible for the prosecution, not who was responsible for the defense. I think this does solve the puzzle of what Frederick Douglas Norman’s role was — though not the puzzle of why he assumed the role.”

Frederick was a Lincoln’s Inn Fields solicitor who had a history of prosecuting these types of sexual immorality cases. At the present time it is unknown if the police, or maybe even the Central Vigilance Committee, hired him. As for Elliot Hutchinson, the Lincoln’s Inn Fields solicitor whom Tumblety featured in his 1893 autobiography, one has to wonder if he was Tumblety’s defense solicitor. £120 per hour isn’t an alluring sum, but that is the price to pay to have the Solicitors Regulation Authority check for any surviving 1888 records for the firms Douglas Norman Solicitors and Hutchinson & Sons.

We have taken a good look at the indictment discovered by Andy Aliffe many years ago. It has been a memorable experience. I personally found it enjoyable to work with an excellent group of colleagues who were very generous with their time.

FOOTNOTES

1. Trevor Marriott’s Doctor at Sea article showed why the indictment would have been authorized on November 19, 1888.

2. http://www.williamsugghistory.co.uk

3. Roger Palmer explained that Frederick’s law partner was Henry J. G. Ross. Their partnership dissolved on December 20, 1890 by mutual consent.

4. Chris Phillips and Chris Scott were instrumental in locating these examples from The Times.

PHOTOGRAPH SOURCES

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3d7/1/1 www.casebook.org

www.williamsugghistory.co.uk/history.htm

http://www.pleasantplaces.biz/authors/webbpeploe_hw.php

http://archidose.org/wp/2003/02/10/women's- library

http://www.opensquares.org/images/lincoln.jpg

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciation goes out to Chris Sugg, Stewart Evans, Roger Palmer, Simon Wood, Chris Scott, Sarah Minney, Robert Linford, and The Women's Library in London. A special thanks goes out to Chris Phillips. And of course, a big round of applause goes to Don Souden for preparing the article for publication in the New Independent Review and Spiro Dimolianis for preparing the article on the Jack the Ripper Writers web site.

(c) Joe Chetcuti 2012

Home

Home